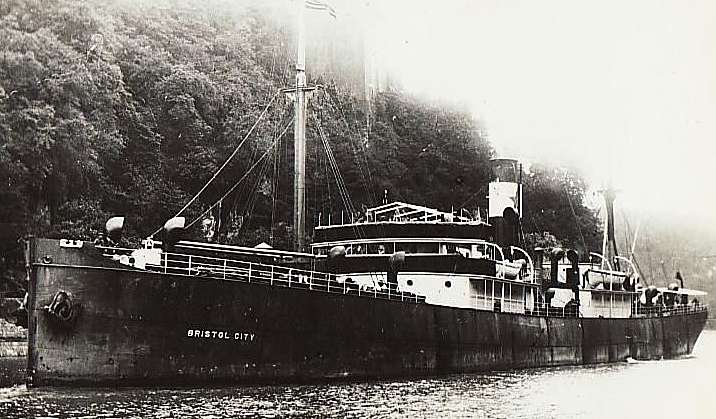

Construction of the East River Drive looking south from 40th Street. (Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives) Construction of the East River Drive looking south from 40th Street. (Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives) When I first read about the Bristol Basin, a swath of English war rubble said to lie beneath Manhattan’s FDR Drive, it struck me as a metaphysically exquisite story packed with symbolism and a kind of elemental, half-believable melancholy. The story — little known even by New Yorkers — latched onto my imagination. A quick online search revealed the general outline: during World War Two, the ruins of Bristol, England were carried as ballast in ships crossing the Atlantic and deposited along the shores of Manhattan’s East River, where they were used as landfill — “hardcore” in construction parlance — during the construction of the East River Drive (now the FDR Drive). The handful of easily verifiable facts are that a plaque commemorating the rubble was installed on a pedestrian bridge at East 25th Street and was dedicated in a ceremony led by mayor Fiorello La Guardia in June of 1942, and then moved in the 1970s to its current location in the courtyard of the Waterside Plaza development, perched over the East River. Beyond that, variations on the Bristol Basin story have accumulated and multiplied during the last eight decades. The many gaps in the paper trail have been improvisationally filled by creative-minded writers fascinated — as I am — by this liminal bit of history, nestled between the obscure and the tedious. Anyone willing to walk to the eastern extreme of Manhattan can find the memorial plaque in plain sight, now on an elevated esplanade at the estuary’s edge at a latitude of about 26th Street. Its mere presence cannot be denied, nor that it commemorates the shattered homes of Bristolians killed and displaced, of family trees limbed by German bombs that rained down on the City of Churches. With new archival information in hand, it’s time to consider again the significance of the English ruins beneath Manhattan’s asphalt. The Birth of Rubble The Bristol Basin’s eponymous city on the River Avon was bombed early and often by the Luftwaffe, killing an estimated 1,300 people and damaging or destroying 100,000 buildings, most of which succumbed to flames sparked by incendiary (thermite) bombs. Six major raids took place between June and September 1940, with additional sorties into December 1940, which is considered the endpoint of the Blitz proper. But the bombing continued with enough regularity and carnage to keep the populace on edge for two more years. On August 28, 1942, the Luftwaffe bombed Broad Weir, a thoroughfare in downtown Bristol, killing three busloads of civilians going about their daily business. This occurred two months after the Bristol Basin ceremony on the East River Drive. While New York politicians dedicated a roadway to the perseverance of the people of Bristol, it was not at all clear that they would persevere. Running a bombed city involves all the civil services as well as a large contingent of volunteers. Citizens jam themselves into shelters (unlike London, Bristol has no Underground to which residents can retire at night during times of war), rumors spread, mistrust in government runs rampant, and class differences are exacerbated. Those who can flee to the countryside, do; those who can’t, stay — and are left to bear up to the shockwaves and conflagrations. The Bristol Emergency Committee was charged with cleaning up after air raids. The first order of business was evacuation of the injured and removal of the dead, along with the ordering of their coffins. Then came dealing with unexploded incendiary bombs, which littered the city by the thousands. Finally, somewhere down the list of priorities, came the clearing of rubble, as detailed in this minutes entry from April 16, 1941: The controller reported that the clearance of roads obstructed with debris was proceeding satisfactorily. He reported that he had recently concluded an arrangement with a Company of Royal Engineers who were prepared to collect up to 1000 tons of hard rubble per day whereby assistance would be rendered in damaged areas following raids to clear debris as quickly as possible. At other times rubble would be collected wherever available.¹ Likewise, minutes of the Bristol Planning & Public Works Committee show that the management of rubble was something of a contentious, if wearisome, issue, as in this entry from January 14, 1941: The City Engineer stated that it was the practice of the Corporation only to clear rubble which had fallen from premises into the highways, and that rubble on private lands was the property of the owners concerned, and that if rubble from damaged premises or sites was placed in the highway it was the responsibility of the owner concerned to clear it way; he stated, however, that in cases where it was brought to the notice of the department that rubble had been in the highways for a considerable time arrangements would be made to remove it.² And once the ruins were cleared? The Register of Letters from the Secretary of Docks Committee hints at the movement of rubble from the city center to the docks of Avonmouth, seven miles west. In June of 1941, the secretary wrote to the dock superintendent and harbor master about “trucks under load with refuse” and “depositing material on banks of the River Avon.” Despite the impeccable order, language, and precision of the various minute books, life in Bristol during the war was anything but ordered and predictable. Armed only with buckets of water they kept at the ready, manual pumps, and hoses, Bristolians were tasked with preventing the spread of fire by dousing those that began in their own homes due to incendiary bombs. Yet many of the residents — up to 10,000 of them at the height of the Blitz — fled to the countryside every night in what came to be known as “Yellow Convoys.” Those who could afford the steep rents leased lodgings from farmers, publicans, and postmistresses. Poorer residents paid a shilling and piled into the back of trucks heading out of town, and sometimes slept in them — or in hedgerows and fields — for the night. Some even took atavistic refuge in caves at Burrington Combe, 15 miles to the south of Bristol³. As with the city proper, conditions were tense at the Avonmouth docks, where blackout conditions were mandatory and most loading and unloading occurred at night under cover of darkness. Many of the documentary logs record violations of the no smoking policy (a lit cigarette could tip off German bombers) and the theft of liquor (I’d need a drink). The heavy influx of cargo vessels bringing in wartime supplies made the dock pilots’ job particularly onerous without dock lights. Collisions were frequent, with damaged vessels sometimes unable to leave port on schedule, taking up valuable space. The conditions were such that in July of 1941 the havenmaster issued specific guidance and training aimed at docking and unloading at night⁴. Working under these conditions, the stevedores, captains, and masters of the docks were likely little concerned with logging the loading of rubble-as-ballast. Noted in the best of times only when it doubled as paying cargo, the ballasting of ships was even less relevant when bombs might fall out of the sky at any moment. In essence, the amount of documentary evidence pertaining to rubble is commensurate with the degree to which it caused inconvenience. Removed from Bristol highways and absent as an object of despair and tinder for argument, the rubble all but ceases to exist in the historical record. And that’s as it should be. No need to commemorate the decimation the enemy has visited upon your city. Let the ruins vanish into the night and never be heard from again. That they should then crop up months later on the other side of the Atlantic seems almost the gag of a cranky absurdist. Perhaps it was. Unless a larger plan was at hand. Hidden away in the “Our London Letters” section of the October 30, 1941 issue of the Nottingham Journal is an inkling: Rubble from “blitzed” British cities no longer appears to enjoy souvenir value in the United States. It is now serving a better utilitarian end without sacrifice of its sentimental appeal. New York has already purchased 3,000 cubic yards of battered Bristol to form the foundations of a drive along the East River. Rubble is hard to get in Manhattan, but our ships going westwards in ballast are glad to take it. The price to New York City is 20 cents a cubic yard, so that so far the ruins of Bristol have bought £120 worth of munitions, besides being able to claim that modern America is literally founded on British soil. By comparison, the rate for landfill used nearly a decade earlier on Robert Moses’ West Side Improvement Project was around $2.50 per cubic yard⁵, according to my calculations about twelve-and-a-half times the price paid for the ruins of Bristol. How and by whom this deal was made, and the total amount eventually purchased relative to the 14.7 acres of landfill used on this portion of the Drive⁶, I could not ascertain⁷. The Ships The news reports of the day indicate that British freighters transported the rubble from Bristol to Manhattan. (While it’s been surmised that American Liberty ships brought over the rubble, this seems unlikely, since the first Liberty ship, the SS Patrick Henry, was launched after the rubble was already in New York.) According to the New York foreign entrance blotters for 1941, nearly 30 ships from Avonmouth anchored in New York Harbor between January and September of 1941, a broad estimate of the timeframe in which the rubble would have been transported. It’s worth noting that the entrance blotters indicate that more ships from Liverpool — also the victim of heavy bombing — than Avonmouth arrived at New York Harbor, which lends support to the idea that the Bristol Basin contains rubble from a multitude of bombed English cities, not just its namesake. As for releasing the rubble where fill was needed along the river, it would have been convenient. Ships used the East River as a causeway to and from the Long Island Sound as they arrived at and left New York Harbor. The goal was to stay inland as long as possible to avoid being sunk by U-boats in open water. Yet despite these efforts, of the 30 some-odd ships that may have brought the Bristol rubble to America, many did eventually succumb. The MV Darlington Court, which arrived in New York from Avonmouth on April 18, 1941, was sunk about a month later, on May 20, on its way to Liverpool. Twenty-eight men perished. The SS Bristol City, which had made the trip regularly since the 1920s, including stopping in New York Harbor on July 28, 1941, met its fate on May 5, 1943 on yet another trip from Bristol to New York. Fifteen of her crew were lost. The MT Empire Steel, which dropped anchor in New York Harbor on June 7, 1941, was torpedoed and sunk by the Italians on March 24, 1942, resulting in 39 dead⁸. If the rubble beneath the FDR Drive is meant to symbolize the losses and bravery of the people of Bristol, it is at least as much a monument to the people whose ships brought it here. It could not have dawned on these sailors, engineers, cooks, and captains that they were carrying in their holds the makings of their own memorial. The Man Behind the Curtain Of all the bit players in the bit story of the Bristol Basin, Stanley M. Isaacs, Manhattan Borough President from 1938–1942, and a member of the city council for nearly 20 years thereafter, had the most to gain from its publicity. A liberal Republican who ran for borough president as the Fusion Party candidate on the La Guardia ticket, Isaacs was known as a steadfast supporter of housing reform, minority rights, and public transportation. His ethical standards were also unassailable. He cut over a hundred patronage jobs in his first eighteen months⁹ as borough president, and saved the city nearly a million dollars in his first two years¹⁰. For those under his dominion, he was known as an efficient and meritocratic manager. The latter of these qualities — his seemingly-naive belief that honest, hard work trumped political affiliation — sank his presidency, and perhaps a totem of his accomplishments was needed to salvage what remained of his career. Isaacs was also an Anglophile, and a member of the English Speaking Union¹¹, the organization that designed, fabricated, and likely paid for the Bristol Basin plaque. His grandfather, Samuel Isaacs, emigrated from England to New York at the age of thirty-five, and eventually became the first rabbi of Shaaray Tefila, the Upper West Side temple then composed mainly of English Jews¹². In correspondence with the English Speaking Union and the Bristol Planning Board, the governing body charged with drumming up Bristol’s image in England, Isaacs leaned on his English roots when promoting the Basin, so much so that English newspapers mentioned that background in their stories about their hometown rubble¹³. True to the Fusion Party ethos, Isaacs chose for his staff men holding a diverse set of political views (however un-diverse their outward appearance). His team included Simon Gerson, a committed communist, to be “Assistant to the President.” Almost immediately, the press walloped Isaacs with unfavorable editorials, picketers lined the sidewalk in front of his family’s Manhattan home, and the American Legion sued to invalidate Gerson’s appointment and petitioned the Governor of New York, Herbert Lehman, to remove Isaacs from office. The Legion’s efforts had little effect at first, merely forcing the change of Gerson’s title to “Confidential Examiner,” a technical update that voided their lawsuit¹⁴. But in late 1940 the enactment of the Devaney bill, which forbade communists from holding public office, was Gerson’s death knell. Corporation Counsel refused to defend him in court, and he lacked the considerable funds to do so himself¹⁵. Soon after the suit was brought, he quit. His resignation came too late for Isaacs: the tumult around Gerson, likely fanned by Robert Moses, whose sensibilities on public welfare ran headlong into Isaacs’, capped the height to which Isaacs’ formidable political talents might otherwise have carried him. On July 29, 1941, the Republican Party chose not to renominate him for a second term as borough president¹⁶. On August 15, 1941, Isaacs issued a press release announcing his withdrawal as a candidate for the borough presidency and his candidacy for a seat on the City Council as an independent: I have always believed that a record of efficient, honest management of the public office — alone and of itself — demands the renomination of the incumbent by all groups interested in good government. The Republican County Chairman has taken the responsibility of deciding otherwise. The present situation has resulted not from any criticism of my stewardship, but rather from the exaggerated importance attached in certain quarters to one incident in my administration, the Gerson appointment …. Even my enemies have attested to the competence with which my office has been run during the past four years…. Accordingly, I now announce my candidacy for the City Council. As a candidate for that office I shall run on my own record without any risk of imperiling united support of the Fusion ticket. I am confident of receiving the full support of those who believe in honest municipal government and true democracy. If he hoped to win that seat he’d have to shake off the communist dross and find a way to garner endorsements . . . and votes. Less than a month after the press release, the story about the Bristol war rubble entered the press and the public imagination. Yet the New York Times wasn’t the only paper to mention the rubble on September 11, 1941. At least four other papers did so on that same day, all with similar language. And they all cite a single source: Manhattan Borough President Stanley M. Isaacs. The Long Island Daily Press: “Rubble from bombed buildings of Bristol, England, were being used today as a fill in construction of East River Drive. Stanley M. Isaacs, borough president of Manhattan, said the debris was brought here as ballast in British ships.” The Daily Argus: “Borough President Stanley M. Isaacs says that earth, rubble and bricks from Nazi-bombed Bristol, England, is being used as fill in the construction of a new stretch of the East River drive between 23rd and 34th Streets.” The pattern continued for days and weeks. The Nassau Daily Review on September 13: “The soil of Britain is becoming an integral part of New York City. Borough President Stanley M. Isaacs says that earth, rubble and bricks from Nazi-bombed Bristol, England, is being used as fill in the construction of a new stretch ot the East River drive.” In England, too, the story was doled out by the British Development Board to regional newspapers, all but one of which cited Isaacs as their source. Though tens of papers eventually carried the story, I found only a single relevant clipping in the Stanley M. Isaacs Papers at the New York Public Library Archives. It’s a mimeographed half-page piece from the September 16, 1941 Herald Tribune with the headline “Britain on the East River”: In need of fill for the final section of the East River Drive, Borough President Isaacs’ engineers have been utilizing ballast brought by freighters returning light from England. Much of it proves to be fragmented brick and rubble — mute evidence of the Luftwaffe’s visits. Before long the carefree and the commuters, business men and families out for an evening drive, will be rolling smoothly and in peace along the riverside on the bones of the bombed houses of Great Britain. There will have to be a marker there for their memory — nothing showy, but a modest tablet of some sort to those dead buildings and to the people who lived and worked in them, who defended them with unshaken courage and preferred to see them smashed to rubble rather than surrender to totalitarian tyranny…. What’s noteworthy about this clipping, other than its lonely existence tucked away among budget estimates, constituent letters, and memoranda, is the following passage, which occurs a little more than halfway through the article (emphasis added): “There is something both moving and symbolic in this transplantation. Had it been done deliberately, as a propagandist device or ceremony in Anglo-American unity, the thing would have been false and pretentious.” That prophylactic defensiveness can be seen, in a less generous light, as an admission of guilt. The stories about the nameless rubble continued to appear in regional papers — The Daily Sentinel, Times Union, Brooklyn Eagle, The Herald Tribune (again), The Times Record — growing more rhapsodic with the months, until June of 1942, when Mayor La Guardia dedicated the tablet in the presence of Stanley Isaacs and numerous officials from both sides of the Atlantic. The rubble finally had its name: the Bristol Basin. The Tablet The parties responsible for the Bristol Basin memorial refer to it in correspondence as “the tablet,” a designation implying divine directives etched upon a granite slab. In reality, the memorial is a simple brass plaque that at the time of this writing is missing one corner screw. Nonetheless, it is the one validating, undeniable artifact to which anyone willing to stroll to the East River can attest. The plaque is now attached to a brick-faced wall in the central courtyard of the Waterside Plaza apartment complex which, in its promotional material, claims to be built on war rubble from Bristol (they’re off by a couple of blocks). The plaque’s inscription reads: Beneath this East River Drive of the City of New York lie stones, bricks and rubble from the bombed City of Bristol in England … Brought here in ballast from overseas, these fragments that once were homes shall testify while men love freedom to the resolution and fortitude of the people of Britain. They saw their homes struck down without warning….It was not their walls but their valor that kept them free. And broad-based under all Is planted England’s oaken-hearted mood. As rich in fortitude As e’er went worldward from the island-wall. The prose was written by Stephen Vincent Benet, and the lines beneath it are an excerpt from “A National Ode,” an occasional poem written by Bayard Taylor for America’s centennial. In 1942, Stanley Isaacs won his seat on the city council, finishing ahead of all Republicans, the party that had treated him so shabbily. During the final days of his presidency, he lobbied the English-Speaking Union to design and fabricate the Bristol Basin memorial, and he now pushed for its completion. Isaacs also made sure to keep one H. V. Hindle of the Bristol Development Board, his public relations counterpart in Bristol, abreast of new developments. That organization’s interest mirrored Isaacs’ — to promote the war effort in the guise of the special transatlantic relationship. “I gather the tablet has probably been erected by this time,” Hindle wrote to Isaacs in January of 1942. This was a hopeful gathering, given that a full six months remained before the tablet would be unveiled. “We should be very glad to have a picture of it,” he added. The timing suggests that Isaacs had planned to cap his presidency with the memorial, but that because of delays in its production he now had no choice but to ensure it was completed nonetheless. In March, Isaacs replied to Hindle: “I was very glad to receive your letter and to see the [English newspaper] clippings. I wish I could tell you that the tablet has already been erected, but the English-Speaking Union has been far slower than I have expected . . . .”¹⁷ After a few more months and fevered exchanges between Isaacs and the English-Speaking Union, the tablet found its home and was dedicated to an audience of about 250 people. “It is a war of all the people of the United States, Britain, China and Russia for their own survival,” Mayor La Guardia said at the ceremony. D.N. Haggard, the British consul, added that the plaque represents “a new mark of sympathy between America and Britain, united in war and shortly, we hope, to be united in peace.” In Isaacs' papers I found a typewritten speech that he had apparently prepared to deliver at the dedication, but it’s not clear that he was given a chance to do so. He was no longer the borough president, after all. While echoing the themes and grandeur of La Guardia’s, Isaacs’ dedication includes a broader set of cohorts: “Those of any race, of any creed, of any nation, who love liberty more than life itself, are our allies in this fight. Together we will attain victory, establish peace, and secure freedom for all mankind, and for generations to come.” Isaacs and his wife, Edith, were invited to join a post-dedication luncheon hosted by the English-Speaking Union in the dining room of the Shell Oil Company at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, an invitation he accepted¹⁸. It’s natural to assume — as others have over the last 80 years — that the tablet is set atop the buried war remnants. But it isn’t. The original location at the terminus of East 25th Street was simply the only anchor available, and the plaque’s current location, apparently selected because of its proximity to the first, is only marginally closer to the rubble. But does it matter? In a letter to the English-Speaking Union dated March 4, 1942, Isaacs wrote that “it was agreed that the best location would probably be the north face of the pedestrian bridge which crosses the Drive at 25th Street. The rubble is actually buried a few blocks further north, but in the exact area there is literally no place where a tablet could be located and seen.” The landscape has since changed. At the time of this writing, 28th Street marks the northern edge of the Waterside Plaza complex. The bare wall of a raised garden presents at least one welcoming facade, should the plaque move yet again. In March of 1946, six months after the war’s end, Helen Carroll, an assistant to Christopher Morley, the editor of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, sent a letter to Robert Moses requesting he identify the person “who wrote the prose and poetry which appear on the plaque at East 25th Street and the East River Drive.” Moses, occupied as he was by massive civil projects while heading up a multitude of city and state agencies, apparently never got the memos — any of them. Like all who happened upon the war rubble on the edge of Manhattan, he had no firm grasp of just how it came into being, nor of where it was located. Moses checked with his sources and replied that “the noble words at the Bristol Basin to which I was merely an accessory, seem unfortunately to be without substantial foundation — I mean foundation in fact, as you will see from the attached memorandum.” That “attached memorandum” was from Arthur S. Hodgkiss, the assistant general manager of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, of which Moses was the chairman. In it, Hodgkiss lets Moses know that the war fill was laid down in the section from 28th Street to 40th Street and consisted of “sand, slag and crushed brick rubble from bombed out buildings in England, the type of material depending entirely upon the point at which the boat had shipped out of England.” In case there was any doubt, Hodgkiss finishes his note by stating that “there is no Bristol rubble or any other rubble at the Bristol Boat Basin. The rubble fill was placed in the section starting two blocks north of the basin.”¹⁹ Moses closes his letter to Ms. Carroll with: “Whether, under the circumstances, you and Chris [Morley] want to include this purple passage in your book is something which I leave to your consciences.” Just a few years after its dedication, the Basin had become, a priori, a solidified (albeit obscure) landmark — sacred material presumed to be buried in a location requiring accurate marking. That the rubble was a couple of blocks north of the plaque seemed altogether shameful. Moses was embarrassed enough to distance himself from the whole shebang by noting that he was “merely an accessory” to the project, while calling out the “purple prose” of the plaque’s inscription. The Bartlett’s editors, apparently heeding Moses’ caution, did not include the tablet’s inscription in the 1948 edition of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations. But they thought it wise to include something from Moses himself: “A tunnel is merely a tiled, vehicular bathroom smelling faintly of monoxide.” Carbon monoxide has no odor, though we may wish to hold our noses anyway. Hronir Underfoot If one were to tear up the asphalt of the FDR Drive, pull core samples, and find therein the crushed bricks of Bristol, would this story become more interesting, or even less? In all the too many newspaper articles, correspondence, log books, photographs, committee minutes, ledgers, entry blotters, cost estimates, and construction plans that I viewed — in both the U.S. and England — I found only vague, uncorroborated references to the transport of war rubble. This may well be because none of the three elements — rubble, ballast, landfill — leave a record. Or it may be that the story is apocryphal. In the Jorge Luis Borges short story, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” we find an antecedent to the Bristol Basin narrative, a fictional one. When the people of the world of Tlön imagine a shared historical past en masse, artifacts from that conjured past manifest themselves in the physical realm, and are soon discovered buried at the very site on which the populace is focused. These objects are called hronir: “The methodical fabrication of hronir . . . has performed prodigious services for archaeologists. It has made possible the interrogation and even the modification of the past, which is now no less plastic and docile than the future.” Before long, the narrator of the Borges story, not unlike the writer of this one, begins to witness the intrusion of this fantastic world into his own reality, until he is unable to pull the warp of one from the weft of the other. Which is to say that the Bristol Basin rubble exists outside the norms of historical constructs. The story itself, a bit of narrative genius whose perpetual unprovability is second only to its metaphoric virtuosity, makes sense in the context of material manifested by believers, based on a narrative seeded by a small cadre of originators. Those originators — and Stanley M. Isaacs in particular — likely had their reasons: to ease America into World War Two, and to warn New Yorkers that the rubble underfoot could one day be the remains of their own homes. Endnotes

0 Comments

|

AuthorGreg Sanders is the author of the short story collections The Suffering of Lesser Mammals and Motel Girl. He lives in Brooklyn with his family. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed